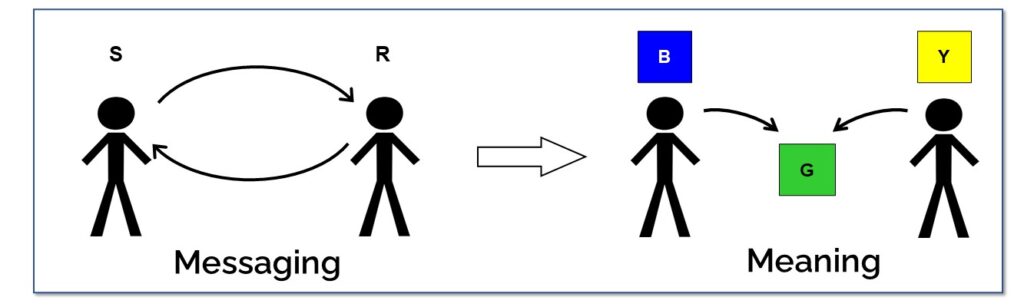

I have a proposal for how you can communicate more effectively, starting today. It involves a subtle but important shift in how you think about communication itself: Instead of thinking of communication as the sending and receiving of messages, think of it as a collaborative act, where you and those you’re communicating with have a clear goal: to co-create shared meaning. Instead of thinking ‘I’ve communicated’ once you’ve ‘sent your message’ (or email, or text, or voice mail), think of this as only a first step, and then follow-up with the next step: taking responsibility for the others’ understanding.

This is about redefining and re-conceptualizing communication from an individualistic activity, to a relational one, in the same way that you with your blue paint, might collaborate with me and my yellow paint, to co-create our green paint. This doesn’t mean we’ll always find common ground or agreement—‘agreeing to disagree’ is sometimes all we can achieve. But the minimum to strive for is mutual understanding, and the higher goal remains: co-creating of shared meaning. You can communicate more effectively, starting today, just by remembering that it’s not about (only) you.

That’s the proposal in brief. If you’re already an effective communicator, you’re probably already doing this. If you’re trying to improve your communication, please give this a try, and let me know how it goes. And if you’re interested in spending a little more time now, on some background and relevant examples, please do read on.

At work, we communicate all day long, in one form or another—verbally/non-verbally, through written documents, during presentations—but we don’t pay too much attention to how we conceptualize communication itself. When you ask people to define communication, the most common response is similar to what’s described above: communication is a process, involving the sending and receiving of messages or information, between a sender and a receiver. That definition is pretty clear, and it’s not immediately apparent that we would even need an alternative definition, or an alternative approach for communication.

But we do.

Because we also know that for most organizations, communication is often poor, and has been for a long time. In a Interact/Harris survey of top complaints from employees about their leaders, 91% of the one thousand surveyed cited ‘poor communication.’[1] The Project Management Institute (PMI), the foremost project management association, reports that “poor communication is the number one reason why projects fail.”[2]

Poor communication is also an expensive problem. David Grossman, CEO of the Grossman Group, has estimated that on average, every large organization (100K+ employees) wastes $62 million annually because of poor- or mis-communication.[3] As for written communications specifically, Josh Bernoff, author of the colorfully titled Writing Without Bullshit,[4] estimates that time wasted by managers making sense of poorly written documents amounts to a “poor writing tax” of $396 billion, exacted on the US economy every year.[5]

Not surprisingly, there’s a near-endless supply of materials and advice on how to improve communication, some of it good and simple, like this: ‘talk less; listen more.’ Most of it, however, is built implicitly on the idea that communication is primarily the sending and receiving of messages or information. So let me say clearly: Despite it being the mainstream view, this ‘sender-receiver’ model is not now, nor has it ever been a very effective model for managerial or organizational communication, or human communication in general.

Strange as it may sound, the sender-receiver model originates from the electrical engineering of the 1940’s and 50’s, when well-intentioned educators and philanthropists wanted to make business education ‘more scientific and rigorous.’ To do so, they imported into the management curriculum various methods, models and theories from the hard sciences, including the model for sender-receiver, which appeared in a paper authored by two mathematicians working on engineering aspects of telecommunications equipment.[6]

While it may have been useful for circuit design and modelling the flow of electrons, and even though it appears in management textbooks still today, the sender-receiver model falls far short of describing or enabling the rich and nuanced potential of human communication. As a model or metaphor for human communication, the guidance provided is limited to the most rudimentary: communicate with clarity, and eliminate ‘noise’ that may obscure the message. Communicating with clarity is good advice, but it’s also a minimum. And no one’s offering opportunities or promotions just because you speak clearly—that’s table stakes. In the remainder of this article, I’ll discuss a couple of the key limitations of ‘sender-receiver,’ propose an alternative—co-creating of shared meaning, which comes not from the hard sciences but the social sciences—and provide some examples.

Perhaps the largest problem with sender-receiver as a model for human communication, is that it focuses on messaging, but makes no provision for meaning.[7] The message—spoken words, for example—and the meanings we attribute to the message, are two separate things. If I want to dim the lights for a presentation and say to a colleague “Can you reach the light switch?” they won’t answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ because we both know that’s not what I mean. Instead, they’ll kindly get up and dim the lights. Back in the days of land lines, if I phoned a colleague and one of their young children answered the phone, I’d say: “Hi, is your dad home?” “Yes,” they’d answer, and await my next question.

The fact that messages and meanings are different—this is one of the tough lessons you learn with your first attempts at public speaking: You may have control over the message, but not over the meanings your audience attributes to it. If you haven’t done so in a while, try actively soliciting some in-depth feedback on your own communications, and you might be surprised what you hear. And if the feedback is anonymous, brace yourself—snark is a hobby for some. These differing interpretations of the speaker and the listener are the source of frustration and miscommunication, but also of innovation, when others bring novel interpretations to what we say or write. As the diversity of the workforce grows, the challenge of effective communication grows—but so too, do the opportunities.

For managing and leading, the meaning often matters more than the message. Meaning is the harder won of the two, and often the more valued. If a manager apologizes to the team for letting them down—”I’m sorry I let you down”—the team is more likely to accept that apology, if the team believes the manager actually means it. And if the team doesn’t believe it, then those very same words (the message) can have the opposite meaning—distrust, demotivation, etc.; the leader’s words are ‘meaning-less.’ If through the manager’s actions it’s obvious they feel bad for letting the team down, sometimes the words (the message) aren’t necessary at all, and the meaning will be clearly communicated anyway. Meaning doesn’t always depend on message, but message almost always depends on meaning—i.e. messages, in order to be understood or acted upon, must be ‘meaning-ful.’

Of the several other limitations of sender-receiver, I’ll mention just one more: it can lead to a lessened responsibility to others. As a ‘sender,’ your primary responsibility is to send messages. According to this approach, once you’ve sent your message, or email, or text, you can indeed claim to have communicated. Unfortunately, we hear this kind of language all the time, particularly when there’s been a misunderstanding: “I communicated all this to you in my email last week. Didn’t you get my message?”

If we expand this a bit, it’s easy to imagine all kinds of communication that are ineffective, but nevertheless satisfy the requirements of sender-receiver. I apologize in advance, Dear Reader, but please take a moment and think back, to some of the worst presentations you’ve suffered through at work, the kind that had you looking for the exit, or excusing yourself to take that ‘important call’ that was actually just an alarm tone that you yourself had set to go off. I saw what you did there.

So what was it that made the presentation insufferable? Was it simply waaay too long? Or too detailed—or perhaps not detailed enough? Maybe the presenter/lecturer didn’t do enough to establish their own credibility with the audience—the list goes on. I’ll guess that for at least some of these presentations, what made them painful was that the presenter saw their primary responsibility as that of sending information and of ‘getting through these slides.’ Tables of numbers; large blocks of text, aka ‘walls of text;’ long lists of ‘key’ points, each and every one of which they covered in depth, methodically, ploddingly; unexplained jargon or acronyms. And if time ran short, instead of wrapping up, they just talked faster, to fulfill their responsibility of transmitting information and ‘getting through these slides.’

So how might they have presented differently, if their purpose was the co-creation of shared meaning? If they took responsibility for our understanding? Here are just a few—let’s tell them directly: Next time, Dear Presenter, if we the audience don’t know you very well, please take a moment to share with us something of your background, to establish your credibility, because context is important, and because understanding itself requires context in order to be ‘meaning-ful.’ Make sure you have a clear purpose (your ‘why’) for making this presentation (more context), and that you explain that right up front. As you present, please read the room. Read our facial expressions and our body language and other non-verbal communications (while staying aware of your own) and make adjustments accordingly, in real time. Instead of expecting us to wait quietly for that dopey, obligatory “Q&A” or “Questions?” slide at the end—like a studio audience that’s told to keep quiet until the “applause” sign illuminates—please stop occasionally and solicit our thoughts. If you’re out of time or some of us are nodding off, please get right to the conclusions/recommendations, or take a break, or simply adjourn and reconvene later if possible.

This is how people present and communicate when they take responsibility for the other’s understanding, and strive not just for ‘buy-in’ to their ideas, but for co-creation and co-ownership of ideas. Effective communicators are respectful of the audience’s time. They talk with the audience, not at the audience. Effective communicators know going in there will be a wide diversity of views and reactions, and thus they see successful communication as a significant, relational achievement, an achievement that is all the more challenging, but also potentially more valuable, whenever different departmental or cultural views or time zones must be brought together.

At this point, Dear Reader, I suspect there might be a need to address this question: If sender-receiver is so ineffective, then how did it rise to become the mainstream? I’ll offer two reasons. The first one is historical, as described above. Communication is just one of several areas where the industrial/scientific/technical origins of management itself, which emerged from the industrial revolution, remain alive and well in organizations. In university management education, for example, only about 10% of the units required for a 4-year degree in management are focused on communication and other social competencies, with the remaining 90% focused on more technical areas. Plus, things that become the mainstream, tend to stay the mainstream; sender-receiver is just how people tend to think and talk about communication. It’s a safe choice, and the vocabulary and idioms are plentiful: ‘make sure your message gets through to them;’ ‘choose the best ‘channel’ for your communication,’ etc.

The second reason I’ll offer for the longevity of sender-receiver is that there are certain situations where it can be employed for efficient communication. Consider the military phonetic alphabet for example: alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, etc. The process of communicating using this alphabet indeed approximates that of sender-receiver. This model works, however, because meaning is fixed (not open to interpretation; “alpha” always means “a”) and because of a prior agreement to those fixed meanings, by those participating in the communication.

Consider a newly formed team in an organization. They meet and begin to get to know one another. If the working environment and team membership are relatively stable, and if they can successfully navigate through some initial conflict and stay engaged, a level of trust may begin to develop. Over time, some team-specific jargon or nicknames may emerge, as will mutual expectations and agreed-upon processes for task completion. In other words, they will have co-created shared meanings and understandings about how to work together. Once the shared understandings are created, communication within the team may become simpler, more streamlined, and amenable to a sender-receiver approach.

The problem, of course, is that for most teams, in most organizations, change is constant. Team membership changes; new members with different backgrounds join, and the once-shared understandings are no longer shared, and must be created anew. The sender-receiver approach to communicating remains tempting, however, because it appears to be so time efficient. Just type up an email or ‘instant message,’ hit the ‘send’ key and voila! You’ve ‘communicated!’ But then misinterpretations ensue, communication breaks down, and the team development cycle and co-creation of shared meanings begins anew.

Given the ever-increasing pace of business change, and the ever-increasing diversity of the workforce, the opportunities where sender-receiver approach can be effective seem ever-fewer and farther between. It’s nice to be a part of team that’s tight enough for it to work, if only for a while. But when we take the bait, and employ it prematurely, and without having co-created any shared meaning; when, after a miscommunication, we allow ourselves to shift the blame with “Didn’t you get my message?”—this is when the trouble starts, adding one more tally to the already-leading reason for why projects fail: poor communication. Co-creating of shared meaning carries an up-front cost in terms of time spent, but can lessen the frequency and cost of later miscommunication.

To wrap-up this up, Dear Reader, here are three guidelines for communicating for meaning not just for messaging.

1. Know your purpose. Communicating is a social act. And just like any social act, in order to be judged effective, or not, you need a purpose. The goal is more than just sending information. So know what is it you want people to do/not do, approve/disapprove as a result of your communication. Open-ended, exploratory or brainstorming communications are fine, of course (see #3 below), just make that purpose known.

2. Know your audience. Communicating is relational. Human meaning itself is relational. For example, to say the color of the sky is “blue” makes sense because we speakers of English have a prior agreement, that when we want to describe the color of the sky, we’ll use the word “blue.” “Blue” is not your private vocabulary, and there is no inherent “blue-ness” to the sky—just ask someone who doesn’t speak a word of English. For humans, meaning itself, like the meaning of the word “blue,” exists in relation with others. If meaning is relational, then you need an audience for co-creation, otherwise it’s just a soliloquy. And the more you know about that audience, the better. If you were asked to present to a filled auditorium, but the lights were off and you didn’t know who filled the seats, what could you communicate?

3. Leave room for co-creation. Just like leaving room for cream in your coffee. Unless you’re communicating in a crisis, and telling people exactly what, why, how and when to do or not do, with no interpretation or improvisation on their own (i.e. sender-receiver), then leave room for, and actively (and sincerely) solicit their contributions to the meaning you are co-creating together. This can lessen the pressure on you; you don’t always have to have it all figured out. Half-baked ideas are often underrated. Generativity[8]—maximizing the participation of diverse inputs and with a future orientation—can move you past filling in the blanks (the ‘known-unknowns’) of your already-existing ideas and frameworks, and on to discovering the ‘unknown-unknowns’—the source of truly breakthrough innovation.

[1]Solomon, L. “The top complaints from employees about their leaders.” Harvard Business Review (2015): 2-5.

[2]Monkhouse, P. (2015). “My project is failing, it is not my fault.” Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2015—EMEA, London, England. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

[3]Grossman, D. (2011) “The cost of poor communications.” Holmes Report: https://www.provokemedia.com/latest/article/the-cost-of-poor-communications; accessed 2/24/22

[4]Bernoff, Josh. (2016). “Writing without bullshit: Boost your career by saying what you mean.” HarperCollins.

[5]Bernoff, J. (2017). “Bad writing costs businesses billions.” The Daily Beast. https://www.thedailybeast.com/bad-writing-costs-businesses-billions?ref=scroll Accessed 2/23/22

[6]The most influential paper was “The mathematical theory of communication,” (1949, University of Illinois Press) authored by two mathematicians, Shannon, Claude Elwood, and Warren Weaver.

[7]The focus on messaging over meaning was not an oversight by the authors, it was simply not the focus of the their work. In a 1948 paper, for example, Claude Shannon writes: “The fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected at another point. Frequently the messages have meaning; that is they refer to or are correlated according to some system with certain physical or conceptual entities. These semantic aspects of communication [i.e. ‘meaning’] are irrelevant to the engineering problem” (Shannon, Claude Elwood. 1948. “A mathematical theory of communication.” The Bell system technical journal 27.3, pp. 379, emphasis in original).

[8]For more on generativity, see 1) my brief Notes on Generativity; 2) Zittrain, Jonathan. (2008). “The future of the internet–and how to stop it.” Yale University Press, 2008; 3) Tajedin, H., Madhok, A., & Keyhani, M. (2019). “A theory of digital firm-designed markets: Defying knowledge constraints with crowds and marketplaces.” Strategy Science, 4(4), 323–342; and 4) Thomas, Llewellyn DW, and Richard Tee. (2021) “Generativity: A systematic review and conceptual framework.” International Journal of Management Reviews, p. 1-24